My Notes on Pawpaws

Ted Ruegsegger

Revised November 5, 2025

The pawpaw is the largest edible fruit native to the United States. Searching the web for “pawpaw” finds all kinds of articles and pictures (it'll also find you lots of references to papaya, an entirely different fruit which some people call pawpaw). Instead of duplicating all that, I'll list my own observations and notes.

How do they taste?

They have a taste all their own—the closest description, and the one you'll read on most websites, is that they're a cross between a banana and a mango. On the one hand, that's completely wrong: eating one doesn't remind you of bananas or mangoes. On the other, it's right in spirit, conveying a sense of rich, creamy texture and sweet, fruity flavor. Another description I've heard is banana and pear.

Also, their flavor varies over time. When they're first ripe enough to eat, the flesh is light greenish-yellow and more banana-like in flavor. As they get more ripe, the yellow color deepens and that “banana-mango” flavor predominates. Finally they get a very deep brownish-yellow and taste like caramel (in the sense of flan, aka crème caramel). Hard to say which I like best but I guess I lean toward the caramel end.

In the wild, once in a while you'll get one that tastes bland or even soapy. Don't write pawpaws off; you just got a bad one—spit it out and grab another.

Why don't supermarkets carry them?

Too perishable. Perhaps they might someday carry frozen pawpaw pulp, which is delicious.

Where do you find them?

If you're lucky enough to live in a region that has pawpaw orchards, by all means pay them a visit. When I started my quest some decades ago, such places were difficult to find, but now that every farm has a web site, a search will quickly show you the ones nearest you. These days, you may even find pawpaw fruit at farmers' markets.

Failing that, you must look for wild pawpaws. Tricky. In theory, they grow all over the US, east of the Mississippi, but you have to know where to look. Once you've seen a pawpaw tree or, better yet, a pawpaw patch, you'll get better at spotting them.

I stumbled on my first wild pawpaws by accident. I knew what the fruits looked like since I'd mail-ordered them for years, so when I saw one lying on a walking path I recognized it. “That's a pawpaw!” I looked around and saw a tree with glossy, tropical-looking leaves just like the pictures: “That's a pawpaw tree!” Then the surrounding trees came into focus: “It's a whole pawpaw forest!” Sure enough, for almost a mile along both banks of a creek in Chantilly, Virginia, the dominant tree was the pawpaw. We came back and easily filled half a dozen supermarket bags with fruit. Every year for almost a month the fruit were there for the collecting—no one else seemed to know or care. I miss the Enchanted Pawpaw Forest. It was the ideal environment in terms of soil, water and drainage. What's more, a symbiotic insect population had arisen that ensured an exceptionally high pollination rate, so the trees bore fruit like mad. A thorough spraying with insect repellent was a small price for such abundance.

Mail-order them? Whence?

Integration Acres will ship you particularly tasty Ohio fruit in season (late August through early October) as well as frozen pawpaw pulp and other delicacies.

How can I be sure it's a pawpaw tree?

Obviously it's no problem if there are flowers or fruit. But a few trees look similar, especially as small seedlings. The leaves alternate along the stems and have a characteristic shape, widest just before their outline reverses its curve and comes to a point. They have no sawteeth along the edges (those are beeches). In the fall, pawpaw foliage turns a paler green while everything around it is still dark green, after which it turns a pale yellow; this makes pawpaw patches readily visible from afar.

If you're still in doubt, crush a bit of a leaf and smell it; if it's a pawpaw, it will have a “gasoline-like” smell (it's about as close to gasoline as the fruit flavor is to a banana, but it's distinctive, an unmistakeable petroleum-distillate odor. Others describe it as a “green bell pepper” smell, and I have to admit that's equally plausible). Another plant, Lindera benzoin, aka northern spicebush or Appalachian allspice, resembles a pawpaw as a seedling and also has that smell plus a sweet, fruity smell like citronella. If you find spicebush, there's a good chance pawpaws are growing nearby, at least in the South. If you find them in the North, plant some pawpaws!

How do I harvest wild pawpaws?

They fall to the ground: pick them up, after checking that bugs haven't got to them first. Gently feel (don't squeeze—they bruise easily) any hanging fruit within reach—if they're hard, leave them to ripen a few more days. To get ripe fruit not in reach, give the tree a gentle shake, then pick up the fruits that drop. Don't shake too hard or unripe fruit will drop. Take them home anyway—they'll ripen on the kitchen counter, not as well as on the tree but still delicious.

Pawpaw trees in the wild can exceed 30 feet in height, so watch your head and shoulders when shaking! When the fruits drop, some will bruise and some will split open. Don't be squeamish—they taste just as good and the unbroken ones won't keep much longer anyway.

I used plastic grocery bags to collect them in the wild; don't fill them more than halfway or the ones on the bottom will be completely squashed. Three bags in each hand was my limit; even then I'd leave full bags next to landmarks to pick up on my return. Carry spare bags since you'll tear some on thornbushes or other undergrowth.

When you get them home, rinse them off in the sink and lay them out on towels to air dry. From the ones that are split or squashed, go ahead and scoop the flesh into a container and put it in the refrigerator. And it goes without saying that those who do the washing and sorting get to eat all they want!

How do I eat them?

Photos usually show them cut in half lengthwise, displaying the rows of seeds. That's certainly a nice presentation but it's a tedious chore poking a knife between all the seeds until you can pry it apart. Perhaps for company, each half placed on a dessert plate with a spoon.

I cut them in half at right angles to the long axis. In fact, the skin is so tender you can nick it with a fingernail and pull it apart. At that point you can scoop the flesh out with a spoon; that's the best way to get every last bit. Outdoors, say while harvesting wild pawpaws, you'll probably just squeeze the contents of each half into your mouth.

Pawpaw recipes abound, for example, two very promising ones in this NPR article. Note that, unlike bananas, which are best for baking when very much overripe, pawpaws peak at the deep-yellow caramel stage and then get pale tan and flavorless. So if you want to bake with them, you have to give up eating some fresh. That said, there seems to be a general consensus that heat diminishes much of the subtle flavors and intensifies less pleasant ones, and that cold preparations like smoothies and ice cream work better. Apparently pawpaws work great in beer, too, but I haven't tried that yet. When I finally make it to the Ohio Pawpaw Festival that will definitely be on the agenda! Speaking of the Festival, they have a cookoff contest every year, but as far as I can tell, never publish the recipes. I'm sure I'm not the only one who would gladly pay for each year's collection!

As of spring 2023 I can testify that pawpaw wine is fantastic. I ordered a bottle from Wildside Winery in Kentucky. [The pawpaw wine can be tricky to find; try this link.] This isn't pawpaw-flavored grape wine, it's made entirely from pawpaws. Wonderful nose, delicious flavor that's interestingly distinct from fresh pawpaw.

Wild pawpaws are delicious! Does it get any better than this?

Yes, as a matter of fact! I can find something to like in just about any pawpaw, but when I finally had some of those named cultivars I got what the fuss is about. After I moved north, away from the Enchanted Pawpaw Forest, I resumed ordering fruit from Integration Acres and noticed a dramatic change in the quality. Whereas they used to pick and ship wild-growing fruit, their orchards are now grown and bearing. It's not practical to label every fruit they ship, but it's very clear that the selected varieties are superior to most wild fruit.

I had for years heard and read of the work of Neal Peterson who bred especially great, named varieties of pawpaw. If you don't already know all about this icon of the pawpaw world, take a moment to browse his website, which includes a link to NPR's excellent introduction to pawpaws by Allison Aubrey. Thanks to Abbie White, who has a pawpaw grove at Whitesfields Farm in Hardwick, Massachusetts and sells the fruit at the Hardwick Farmers' Market, I had my first taste of Peterson's Shenandoah and Susquehanna varieties. Mouth-watering, deeply satisfying, with a bonus that there's much more flesh and fewer seeds.

Can I grow my own?

You can and you should. If you want named cultivars (and you do), you must buy grafted trees. In that case, unless you have a wild pawpaw population nearby, be sure to plant more than one variety since, like apples, pawpaws usually can't pollinate themselves or close relatives. After years of starting my own seedlings and planting them around my property, I now have four Peterson trees happily growing in my yard. Besides guaranteeing excellent fruit, these grafted trees give me about three years' head start compared to seedlings.

A few years back I purchased a seedling tree from Tripple Brook Farm. The tree, already growing in the ground at the farm, moved to my yard with no apparent transplant shock and appears to be thriving, giving the lie to the widespread belief that transplanting a pawpaw is sure death. But beware, that belief is well-founded: the reason the transplant worked is that the Tripple Brook Farm folks have special equipment to extract and secure the root ball without damaging the fragile taproot and root hairs.

That tree grew from less than three feet to over eleven, flowering at last in the spring of 2014, then grew to over fifteen feet before top-pruning.

Share the bounty?

I have undertaken to restore the pawpaw to as much of New England (well, at least central Massachusetts and nearby Connecticut) as I can. It's still not clear to me where pawpaws originally grew. Maps abound purporting to depict the “native range” of the tree. If some of them are to be believed, pawpaw trees somehow knew about—and wouldn't cross—certain state boundaries, thousands of years before there were any United States! I understand that “native” means “without human involvement”, but since the native Americans (I can't help nitpicking that, since our species originated in Africa, they must not be “native” either) loved pawpaws and spread them everywhere they went, how does anyone really know where the pawpaws grew before that happened? Since pawpaws clearly grow and bear fruit in at least the western part of Massachusetts, could they have been here in the past? Recall that the New England settlers cleared most of the original forests for farmland; only since the mid-19th century have the forests returned. Since pawpaws favor riverbanks and other areas with a reliable water supply, also known as fertile bottomland, they were likely wiped out by farmers wanting this valuable terrain. Many conifers and hardwoods came back on their own, perhaps spreading from adjacent intact habitats; evidently pawpaws lacked that advantage. Perhaps, given a few more centuries, they would have made it back themselves, but for now, enthusiasts like me will give them a little help.

So far, almost sixty little pawpaw patches have sprouted where I planted seeds, mostly just by sticking them in the ground. There's now even a pawpaw patch on Mt. Tom!

Update, September 2016: I finally made it back, four years later, to see my pawpaw seedlings on Mt. Tom, along the M&M trail. Yikes! I didn't recognize the site at first, devastated by the vicissitudes of weather, in particular the October 8, 2014 microburst. After a long search, I found one 7-in seedling (confirmed as a pawpaw by the smell of a torn leaf) and possibly two smaller ones (unconfirmed, since they didn't look like they could spare any leaf) peeking out from under a pile of downed trees. Why still so small? My theory is that the top growth was crushed in the general wreckage and the rootstocks had to start over with fresh shoots. In any case, they'll grow slowly in this overly shady spot, and this summer's drought probably didn't help either. But they're alive!

Update, August 2019: Two healthy seedlings, one a foot tall and the other six inches, growing slowly under that heavy foliage canopy but growing nonetheless.

If you live in a region lacking abundant pawpaw patches, I encourage you to plant seeds in likely places.

You can buy seeds a lot more cheaply than seedlings (well, if you count your own time and labor as free). If you already have some tasty fruit, by all means save the seeds, being very careful not to let them dry out, and grow them.

How do I sprout seeds?

As your web search has told you, they need a few months of cold, must not dry out, and are slow to germinate. Once they germinate, the long taproot and the root hairs are so fragile that damaging them will kill the seedling.

In the past I've stratified seeds in the refrigerator over the winter and then started them in shallow flats with transparent bottoms so I could spot each sprouting seed and move it either to its final bed (in warm weather) or into a tall pot (when it's cold outside). This is tricky and tedious.

I'm now convinced that by far the best way to propagate pawpaws from seed is to plant the seeds directly in the ground where I want the trees to grow. For fresh seeds, this means in the fall when I get them from fresh fruit. They'll stratify over the winter and then sprout the following summer. Leftover seeds can go in the refrigerator and get planted the next spring. After revisiting the places I've planted seeds in the wild, I find the germination rate for seeds popped into the ground is surprisingly high, at least here in central Massachusetts.

Where's the best place to plant them?

My observations of wild pawpaws in Virginia suggest that water is the key. The Enchanted Pawpaw Forest was apparently ideal. The creek (stream, run, branch, lick, Southerners have a zillion names for flowing water while New England has just rivers and brooks) was large (the bed was 30 to 50 feet across and about six feet deep but I rarely saw it anywhere near full, so that must have been erosion from storm runoff) and never went completely dry, even in the worst summer drought. The banks were 4 to 5 feet above the water level, wide and flat. Pawpaws supposedly need good drainage but these flats would have standing water for several days after a hard rain and mud for a few days more. Of course, that whole region seems to be mostly red clay so “good drainage” is relative.

Pawpaws in nearby forests looked healthy and flowered abundantly in the spring but bore little or no fruit. I used to think that was because they just ran out of water during the dry summer, at least during the few years I noticed they were there, when we had steadily worsening annual droughts. But another possibility is that these were clonal pawpaw patches, all “suckers” of the same individual, with no genetically distinct tree nearby for cross-pollination.

Find a place that won't dry out in the summer, like a stream bank or the area adjacent to a pond or wetland, and place several seeds (preferably from different trees, for cross-pollination) in the ground, an inch or so deep. Use photos, GPS coordinates or detailed descriptions and measurements to be sure you can locate the seedlings the next summer or fall amid everything else that will sprout in the same area. Bear in mind that you won't see any topgrowth until a few weeks after germination, since the taproot grows about a foot during that time. Or else just wait a few years until the sprouts are big enough to notice easily; it seems to me that young seedlings grow about six inches per year, more later on. If possible, try to keep the immediate vicinity clear of weeds, because they raise the humidity and can encourage fungus on young seedlings.

Some sources say shade is important for young trees. That may be true for rows of little trees in a sun-drenched orchard but I've noticed that trees planted in the shade grow way more slowly than those with at least partial sun (one of mine had barely reached a foot after five years), and those with full sun don't seem to suffer, at least not here in the North. In any case, when it's time to bear fruit, sun is good.

An excellent modern reference is the KYSU Pawpaw Planting Guide.

What about pollination?

Pawpaws don't attract honey bees, depending instead on less efficient native pollinators like flies and various bugs. Self-sufficient ecosystems like the Enchanted Pawpaw Forest manage to set up their own pollinator populations—I don't know which of the insects did the actual pollinating but the place was a haven for chiggers, biting flies and gnats that kept flying into our eyes. Nothing DEET couldn't handle but not what you'd want in your yard.

One popular strategy is to hang carrion or other odorous items on or near the trees to attract flies and beetles, but I have pets and neighbors I like, so I use another, more labor-intensive approach. I pollinate them by hand with a fine paintbrush, going from tree to tree to ensure the required cross-pollination. Note that pawpaws are extremely fertile, perhaps to compensate for scarce pollinators, so the yield will be well worth the extra trouble. SFGate's How to Hand Pollinate Pawpaw Trees provides detailed guidance and a discussion at Ourfigs.com has some excellent photos distinguishing male and female flowers [Thanks to fellow enthusiast Alex DePillis for these two references, replacing one that vanished]. When my first tree finally bloomed, that's what I did.

Maintenance?

Deer don't eat pawpaw seedlings, bark or foliage; nor do goats. This gives pawpaw trees an advantage in the woods and on farms. A correspondent cautions me that, when the deer need to rub their antlers on tree trunks, pawpaws are as susceptible as any, so protect the young ones.

Almost nothing bothers pawpaw trees. Where pawpaws are plentiful, the larvae of the Zebra Swallowtail butterfly feed on the leaves, but not enough to do the trees any harm (probably this makes them toxic or bad-tasting to predators, like monarch butterflies with milkweed). I have noticed Japanese beetles and spongy moth larvae nibbling some holes in some of the leaves, but they give up quickly, too. This tree has fantastic defenses!

All you really need to do is:

- Ensure they don't dry out.

- Remove branches that might break under snow load.

- Top-prune them to keep the trees a manageable height.

Abbie White's trees have trunks as thick as my leg. Trees like that would be thirty feet tall in the wild, but hers are ten to twelve feet, tops, with sturdy branches and fruit within reach.

If a tree bears unsatisfactory fruit, leave it in place as a rootstock and graft a better one onto it! I read this somewhere and realized by hindsight it was obvious, but a great idea just the same. Since I've planted lots and lots of seeds of unknown quality, I guess I'm going to have to learn how to graft! Bear in mind that pawpaw patches spread by suckers from the roots, and these will be from the rootstock.

A reliable source?

A recognized authority on all things relating to pawpaws I most certainly am not! But I've learned some things, unlearned some widespread but wrong notions, and gradually come to a level of understanding I wish I had long ago. So I'm sharing.

A few decades I ago I kept reading about pawpaws and vowed that I would taste one before I died. At the time, the only way to get any (in New England) was to grow a tree, and I made several failed attempts. When we moved to Virginia I started some seeds, got one to sprout and planted it in the yard, whereupon I finally saw my first pawpaw tree. Long before it was big enough to bear, we moved.

Then came the World Wide Web and Integration Acres and I finally got to taste a pawpaw. In early September 2005, many mail-ordered pawpaws later, I passed by our old house and saw that my pawpaw tree had fruit! That was the first and, for almost a decade, only fruit from a tree I planted. Alas, the new owners had no interest in pawpaws and cut the tree down soon after.

A month later I discovered the Enchanted Pawpaw Forest and my pawpaw education took off. When we returned to New England I wrote up what I'd learned, put it on the web, and was amazed at the response I got. Many readers turned out to be Virginia neighbors I'd never met (but whom I hope to meet on my next visit). As my “Johnny Pawpawseed” activities gained momentum, more and more responses came from New Englanders with similar interests.

So here I am, a lover of the fruit and the tree, a passionate advocate for restoring both to their rightful place. My last yard had sixteen pawpaw plantings, some grafted, some seedlings. I've helped friends and neighbors establish their own trees. In the wilds of central and western Massachusetts I've planted seeds in about 150 places so far, of which almost sixty have sprouted into seedlings.

Fruit at last!

In the spring of 2014, I noticed something new on my largest tree: little fuzzy bumps on some of the branches. Yup, flower buds! After what seemed like an aeon, they became actual flowers.

As soon as my flowers started ripening, I was off to Whitesfields Farm with a fine paintbrush to collect pollen from Abbie's pawpaws.

After several days of careful hand-pollination, I started to see changes in the flowers, as the ovaries swelled and the petals fell; within a week I started seeing baby fruits. More and more appeared, and soon I had a cluster of six tiny fruits, a couple of clusters of four, some threes, and some twos and singles, over twenty baby fruits in all, barely more than half an inch long.

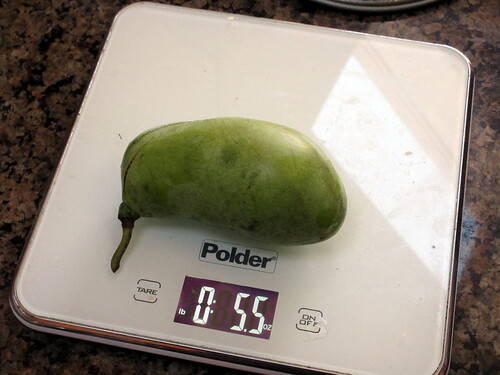

I didn't know it then, but that was pretty much the high point. After a while there seemed to be fewer fruits, but since the leaves were now filling out I thought perhaps they were just harder to locate. Then I saw a couple of my precious babies on the ground! Birds? Squirrels? No, just my continuing education about pawpaws: a phenomenon called fruit drop. If the tree has set more fruit than it can bring to maturity, it will shed the excess to accommodate its resources. My tree, although it was now ten feet tall, was still only three inches across at the base of the trunk. It's probably more complicated than that, taking into account the available water, sunlight, and soil fertility. By July only a single fruit remained. Fortunately for my sanity, that pawpaw did survive until it finally fell from the tree at the end of October. Even so, it hadn't fully ripened, so I guess the tree knew what it was doing—instead of twenty immature fruits, it made one with viable seeds. I let it ripen on the counter for a week; it was edible, but surely I could expect better as the tree matured.

On the other hand, I can finally say I've eaten fruit from my own pawpaw tree!

Two Years Later

Now it was 2016 and the trees were maturing surprisingly quickly. In the spring I was pleased to see sixteen baby fruits on my trees, plus two on my neighbors', but gloomily expected them to drop any day. Instead, they all survived. They swelled to the size of hen's eggs and then stayed that size for much of the summer, probably owing to the drought despite my watering them from time to time, but as fall approached they started swelling.

The champ was a seedling from a Sunflower, which had grown to 10½ feet and had nine fruits, including a cluster of four.

But my grafted Shenandoah, shown above but now 7½ feet tall, was living up to its reputation as a heavy bearer (and early–it was barely taller than I was!) with a quad and a pair, and those are noticeably larger than the others.

Another change was gradually making itself known: what was just a yard with a few pawpaw trees planted in and around it was now taking on the appearance of a pawpaw orchard.

2017: My Last Hurrah

This was the year my trees came into their own. Forty beautiful and delicious fruits, half of them from my young Shenandoah, six more from the newly-bearing Potomac. And all this while a spongy-moth plague stripped most other trees. At this rate, I'd guess next year's harvest will need to be weighed instead of counted!

Sadly, this was also the year we sold the house and moved. The new owners know and appreciate pawpaws, so the effort didn't go to waste.

And a Fresh Start

No, not wasted at all. With my lessons learned, I started over at the new house. I read that grafted trees in pots can be planted in the fall, so I ordered eight named varieties right away. I planted them in my new yard, not without trepidation, since the young trees looked so thin and fragile and, as fall turns to winter, the winds blow hard and cold. Would the graft unions survive until spring?

Spring 2018

I watched gloomily as the winter frosts and storms raged over my tiny trees and turned their beds to pools of ice, steeling myself to start over in spring. To my astonished delight, all but one shrugged it off, leafing out vigorously. In May, the replacement and seven more trees arrived. I should take a moment here to praise One Green World for their fantastic packaging. The eight trees were underway with UPS for almost a week, and arrived in perfect condition, each pot snugly wrapped in plastic and braced against the opposite end of the box with a bamboo stake, so everything stayed put no matter how the box was rotated or bounced around.

So now I have fifteen pawpaw trees including, at last, all six Peterson varieties. With any luck at all, I'll have my first fruits in five or six years. Only after they were all planted did another thought occur to me: What about in ten years, when I have hundreds of pounds of fruit? Farmers' Market? Local food bank? Plus I'll get to try out all those pawpaw recipes for which I've never had enough fruit before.

2020: A Deadly Spring

It seems my worries about too much fruit were premature. Something is killing my pawpaw trees.

2019 saw some partial failures. Maria's Joy had lost its grafted top in spring, though the rootstock sent up several healthy stems. Rappahanock was sickly all through the season. Overleese, twice broken, continued to recover with new growth, if slowly. OK, such things happen.

But 2020 was disastrous, the more so because the spring started out as expected: the pawpaws all started leafing out, many had flower buds, and NC-1 actually kept the flowers to maturity, despite being well under three feet tall.

Then, mysteriously, leaves started wilting and twigs started withering. No big surprise that Rappahanock and Overleese finally gave up, but Allegheny, Benson, one of the Susquehannas, and Wabash had been strong all along, then were completely bare by early June. Potomac and a Shenandoah soon followed, dead by mid-July.

At first I worried it might be something deep down in my soil that harmed the trees when their roots reached down that far, but then I saw that, without exception, all the dead trees have vigorous shoots coming up from the rootstocks! So my soil is ok, but it looks like a surprisingly large number of grafts have failed.

Where I was looking forward to fifteen named varieties, I now have six, plus eight vigorous rootstocks. I contacted One Green World to ask about their rootstocks, in hopes that they might be of sufficient quality to be worth keeping, but they never replied.

2021: New Hope

Now it's January, my grafted tops are still dead, and the vigorous rootstock shoots are all dormant for the winter. To my delight, my Sunflower is covered with flower buds. Pennsylvania Golden has a few, but I might be borrowing pollen from my neighbor. A few of the smaller trees have flower buds but are way too small to make fruit.

2021: Hopes Realized

Mid-September, and Sunflower and Pennsylvania Golden are bearing beyond my expectations. Amazingly, Pennsylvania Golden, the smaller of the two, is the champ, with several dozen good-sized fruit in clusters of as many as six. I guess all that pollination with the paintbrush paid off (besides those two, a Shenandoah and an NC-1 had flowers and donated pollen).

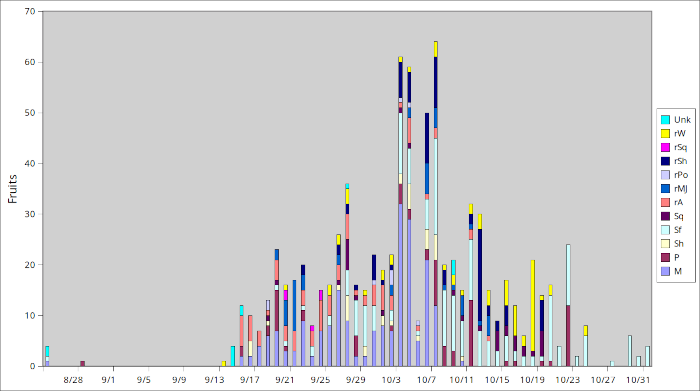

Looking back in early November, those two trees did themselves proud. Between Sep 15th and Oct 1st, Pennsylvania Golden yielded 44 absolutely delicious, medium sized (up to 9 ounces) fruit, dropping to the ground as they became ripe. From Oct 1st to Oct 21st, Sunflower took over with 18 large (up to 12½ ounces) fruits, dropping them just before they were ripe. Beyond my expectations, indeed!

And both trees are covered with flower buds for next year.

2022: The Flood Begins

Spring was again promising. Six trees flowered; the two smallest provided pollen but I didn't expect them to set fruit (nor did they). A Susquehanna was still on the small side but I had hopes (again, no fruit). Mango, one of my two largest trees, had what looked like a fair number of flowers and, of course, Sunflower and Pennsylvania Golden flowered like mad. I got busy with the pollen-paintbrush…

…perhaps too busy, in the case of Pennsylvania Golden, which set so much fruit that at times it looked like it had more fruit than leaves. Branches were bent low from the weight, and two of them actually snapped (they did manage to hang on by a few fibers, keeping the leaves green and actually ripening the fruit).

Sunflower also produced lots of fruit. Mango surprised me; apparently there were many flowers I hadn't noticed, but which got pollinated anyway, presumably with the help of some flies or beetles. Very tasty fruits with a high flesh-to-seed ratio.

I soon realized I was going to have way more fruit than last year. Time to re-read Sara Bir's The Pocket Pawpaw Cookbook. First thing I learned was that, since fresh pawpaws are so perishable, recipes very sensibly start with frozen pawpaw pulp. Lacking (so far) a food mill that can handle pawpaws, I simply extracted pawpaw flesh from the skins and then removed the seeds, one at a time. Some recommend removing the seeds after freezing the pulp; I tried that but it turned out to be way more bother than simply removing the seeds at the start (which is tedious enough but not unpleasant, and can be done while my mind is on other things). I use a fork and a teaspoon; how they work together quickly becomes obvious.

I soon realized I was going to have way more fruit than last year. Time to re-read Sara Bir's The Pocket Pawpaw Cookbook. First thing I learned was that, since fresh pawpaws are so perishable, recipes very sensibly start with frozen pawpaw pulp. Lacking (so far) a food mill that can handle pawpaws, I simply extracted pawpaw flesh from the skins and then removed the seeds, one at a time. Some recommend removing the seeds after freezing the pulp; I tried that but it turned out to be way more bother than simply removing the seeds at the start (which is tedious enough but not unpleasant, and can be done while my mind is on other things). I use a fork and a teaspoon; how they work together quickly becomes obvious.

As the bowl fills with seedless pulp, fill sealable bags a cup at a time (between 250 and 280 grams), flatten and freeze.

As the bowl fills with seedless pulp, fill sealable bags a cup at a time (between 250 and 280 grams), flatten and freeze.

Not surprisingly, all this abundance came to the attention of our local wildlife. In the past, an occasional fruit would wind up on the ground with some bites taken out of it; this year was no exception. I didn't begrudge the critters a share since I had plenty. But then things ramped up: They started taking every fruit just before it got ripe, the moment it changed from “rock-hard” to “firm”. Eventually they were taking the ones growing above my head! There were still a few nibbled fruits on the ground, but most simply vanished.

This gives me an excuse to buy a wildlife camera, or even two, for the next season; turns out they're much cheaper than I thought (apparently the main expense is in replacing the batteries).

Pawpaw harvest this year (not counting what the animals took) was 150 fruits totalling a bit over 46 pounds. Next year's to-do list will include setting up with the local Farmers' Market, since these trees are getting bigger and more productive each year, and I have many more trees that look close to bearing.

I even got some publicity for my growing orchard and my seed-spreading efforts: Sarah Faber of the Harvard Crimson interviewed me via Zoom and wrote an excellent article.

2023: Oops

This year, I under-pollinated. With last year's branch-breaking fruit load still fresh in my mind, it seems I was too cautious. I did my pollination passes on several days in a single week, as opposed to several weeks, and it looks like that wasn't the optimal week. I wound up with far fewer baby fruits than I expected, and figured I'd be lucky to get several dozen pawpaws.

On the other hand, I kept finding more fruits in places I couldn't have reached with the paintbrush, so the insect pollinators must be stepping up their game. I took some more cheer from my efforts to pollinate a solitary pawpaw tree at Smith College, which then bore a baker's dozen plump fruits.

Sunflower, Pennsylvania Golden and Mango fruited again this year and were joined by Susquehanna (only two fruits, with the animals taking one) and two of the rootstocks. Total harvest this year (again, not counting what the animals took) was nowhere near what I'd hoped but better than I had feared, 58 fruits, a bit over 22 pounds.

Many of the trees were now getting tall, which called for some top-pruning (at 12 feet). My yard is again looking very much like an orchard.

2024: Too Much?

This year, with the lessons of the last two seasons in mind, I didn't under-pollinate and tried not to overpollinate. I was now better at recognizing female flowers, and way more trees flowered, all six named varieties and almost all of the former rootstocks. As of early September, I have hundreds of fruits of all sizes. They're still hard as rocks, but they should be ripening soon. And yes, some of the trees are so overloaded I had to add suspension lines to hold the branches up and keep them from breaking. My Pennsylvania Golden seems most susceptible to this problem, partly because it lost some branches a while back and because it fruits like mad.

Plus all the trees have grown considerably since last year, not just up, but out! They're shading out my tomato plots and also obstructing passage between the trees. The trunks are ten feet apart but I have to fight my way through the branches just to check on some of them. I'll need to do some severe pruning at season's end.

As of September 18th, my pawpaw fruits are available at two local farmers' markets: Jen and Jim of Flora and Fauna Farm sell them at the Easthampton Farmers' Market (Sundays 10-2 through Oct 13 at Easthampton City Hall, 50 Payson Ave) and the South Hadley Farmers' Market (Wednesdays 2-6 though Oct 2 at Buttery Brook Park, 123 Willimansett St, South Hadley). It looks like I'll still be having fruit well past the end of the farmers' markets. I'll probably work something out with Jen and Jim to keep them available.

Lessons Learned

Gardening vs Farming

The biggest lesson I learned this year was about quantity. My original goal was to have enough fruit to enjoy and to share, plus some to use in various recipes. Seven years ago, with so many great cultivars to choose from, how could I resist ordering all six Peterson varieties? And there was all this space going to waste as lawn, so of course there are other names that won prizes at the Ohio Pawpaw Festival, plus famous old favorites. Next thing I knew I had fifteen trees. One died, and eventually a bunch of grafted scions failed, so I was left with six named varieties, plus eight vigorous rootstocks.

I had no clear notion how much fruit mature trees will bear. By hindsight, three trees would have sufficed! Now I find myself in the role of a farmer, with none of the skills but increasing responsibilities!

Named Cultivars or Seedlings?

There's no denying that carefully curated named varieties are in many ways superior to random wild pawpaws. Besides consistently good flavor, they tend to have larger fruit and a higher flesh-to-seed ratio. Of course, like apples, they need to be grafted onto rootstocks. Planting grafted trees also gains two or three years over starting from seed.

Grafts can fail. But it turns out that's not so horrible, since the rootstocks very likely started as seedlings from tasty fruit from a pawpaw orchard, so they already have a genetic head start over wild trees. I was delighted to find that when the rootstocks under my failed scions bore fruit of their own, it was excellent, in some cases offering delightful scents and flavors that set them apart.

It follows that planting seeds from tasty fruit should result in healthy trees that bear tasty fruit themselves.

I also note that pawpaw trees send up an enormous number of root suckers, all sprouting from rhizomes sent out from the rootstock. They can grow and bear fruit themselves in the wild but in a cultivated orchard they make it difficult to get around!

Pollination

When the trees are young, with a moderate number of flowers, hand pollination helps to encourage fruiting. Even so, the size and foliage density of each tree matters; don't over-pollinate smaller trees. If they set too much fruit, cull the excess quickly.

As the trees mature and the local insects acclimate to their presence, hand pollination becomes less necessary.

Critters Stealing Fruit

I worried about that once my trees started bearing fruit, but now that the mature trees have hit their stride I barely notice what they take.

I take that back. My Shenandoah tree had a fair number of large, beautiful fruits that seemed close to ripening. Today I checked and every single one was gone without a trace! Clearly something bigger than squirrels.

Preserving Fruit

Since fresh fruit is only briefly available, recipes mainly call for frozen pawpaw pulp, typically in one-cup amounts. The most efficient way to separate the seeds from the pulp uses the nylon “dough blade” of a food processor. I had my doubts, but my vendor partner Jen tried it and convinced me. It works beautifully! Scoop out the insides of a fruit with a spoon and fill up the food processor bowl. A few pulses and voila! a smooth puree with completely detached seeds. Pour that into a colander and stir, leaving seeds in the colander and puree in the vessel below. I still freeze them flat, a cup (300g) at a time, in 1-qt sealable bags, laid flat; Jen uses pretty containers for sale in the winter farmers' market.

Interview

Today, October 10, Clinton Conley of WCVB Channel 5 Boston visited with cameraman Bob to interview me about my orchard, my history with pawpaws, and my “Johnny Pawpaw-seed” activities. We spent a delightful morning and ended up planting pawpaw seeds in the wild! The segment should air sometime in November.

My friend and wild-food connoisseur Blanche Derby has an excellent video that covers a lot of frequently-asked questions about pawpaws.

End of 2024 Season

Sunflower held on to its fruits the longest; I picked the last four November 1st, since the leaves were mostly gone.

2024 stats: 845 fruits for 276 lb (assuming same average weight as the past two seasons) Aug 25 to Nov 1, with the main harvest Sep 14 to Oct 25. And next year's flower buds are popping out all over!

My interview with WCVB Channel 5 Boston aired on Halloween night. The segment also highlights Holyoke's own Nuestras Raices and Aponte Farm.

June 2025

Still a bit worried about overloading the trees, this year I thought I'd hold off on hand-pollination and let my local pollinator population strut their stuff. So far it looks like they've been pretty busy.

This early, it's a bit hard to predict how much fruit will remain on the tree to ripen, but we seem to be off to a good start:

On the other hand, excess fruits are starting to drop:

July 2025

Looks like my local flies, bugs and spiders have not only taken up the burden, they seem to have done a more thorough job than my poking paintbrush. This year, well past the fruit-drop stage, I'm seeing numerous clusters of four and more fruits.

Some of my trees have enough fruit load that I've had to support the branches with suspension lines, but so far none seems in danger of breaking.

September 2025

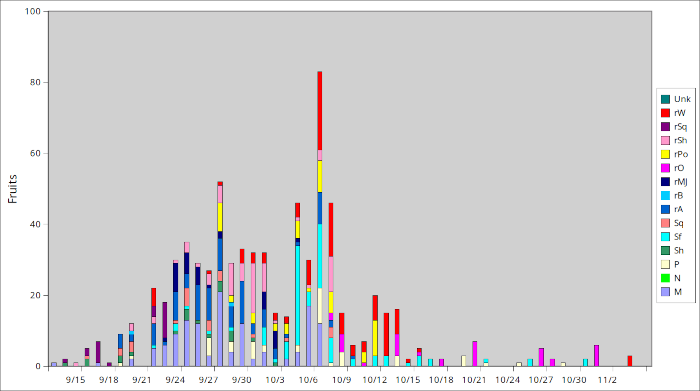

Mid-September, and the first few ripe fruits have arrived, consistent with last season. Not sure how quickly the rest will ripen, since the trees are very heavily loaded and the weather this summer has been strange. A few dozen unripe, rock-hard fruits have fallen. But it's now time to start every day harvesting pawpaws.

And here's the autumnal equinox, the start of fall, and the harvest is in full swing. I'll be taking them to the Farmers' Markets in Holyoke, Easthampton, Northampton, and South Hadley.

October 2025

The harvest is still going strong, but Farmers' Markets are drawing to a close. Thanks again to Jen and Jim of Flora and Fauna for spreading the word (and the fruit) in South Hadley. Karl Prahl of Underline Farm will still offer my pawpaws for the Sunday market in Easthampton through Oct 12th and the Tuesday market in Northampton through Nov 11th.

Greta Jochem of the Springfield Republican interviewed me, visited my orchard and then wrote a great article about lots of us local pawpaw growers.

mid-October 2025

I should have fruit for the Oct 21 Tuesday market in Northampton, but it looks like this season is ending a bit sooner than last year's.

End of 2025 Season

This year's harvest was slightly smaller than last year's: 739 fruits for 242 lb (assuming same average weight as in past seasons), Sep 13 to Nov 4, with the main harvest mid-September to mid-October.

As it Turns Out, Something Does Bother Pawpaw Trees

Alas, I expect next season's harvest to be somewhat smaller, since four of my trees appear to be afflicted by one of several viruses that I've recently learned attack and eventually kill pawpaw trees. Abbie White's pawpaw blog has details and pointers to scientific papers about Tobacco ringspot virus (TRSV), Tomato ringspot virus (ToRSV) and Phytophthora (Phyt). Search for “Pawpaw Tree Health Status”.

So much for my cheerful observation that “Almost nothing bothers pawpaw trees.” I take some comfort in the fact that the four afflicted trees are in a separate part of the yard from the rest, so perhaps the virus won't spread to the others. But goodbye Sunflower, Pennsylvania Golden, a rootstock that just started to bear, and NC-1 that hasn't yet borne.